There has been a remarkable intersection between video games and musical performance this year, from villains lending vocals to their own theme tunes to interactive songs

Toward the end of Baldur’s Gate 3, widely considered the most outstanding video game released this year, you can literally go to hell. If you do, you’ll have a showdown with the game’s equivalent of the devil, a charismatic yet demonic trickster who calls himself Raphael.

It’s one of the toughest, most dramatic encounters in the game, the culmination of 150 hours of play. Naturally, developer Larian Studios wanted it to feel monumental. So they decided that the battle should be accompanied by a song, and that Raphael should be the one singing it. “The idea for a song to be performed by Raphael himself came from our director Swen Vincke about six months before the release of the game,” says Borislav Slavov, Baldur’s Gate 3’s music director. “The team instantly loved it.”

Baldur’s Gate 3 has a big orchestral score, as you’d expect to accompany an epic fantasy tale. But Raphael is more than just a powerful adversary. He’s wry, cunning, narcissistic, and has a taste for the theatrical. Slavov, a lover of West End theatre, began to wonder if there was another way to approach this particular part of the soundtrack. “The moment the lyrics landed on my desk, I realised that there was one thrilling way to go – a full blown musical number.”

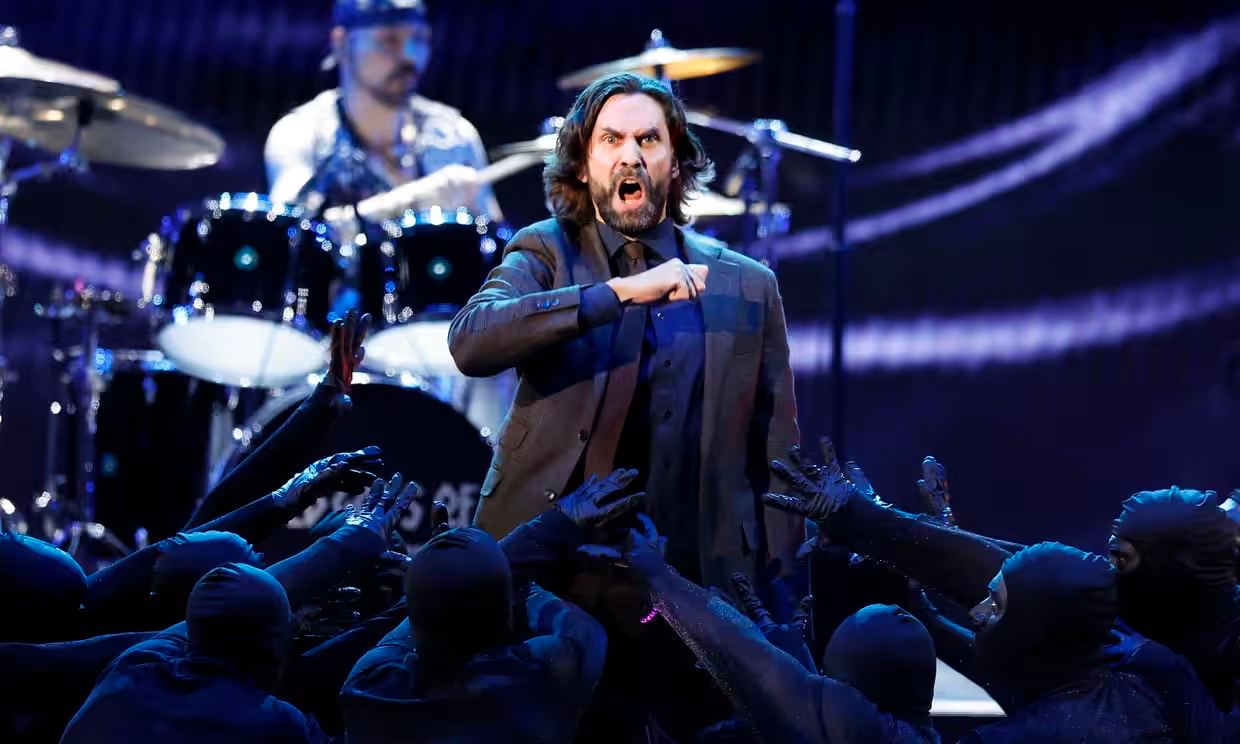

The result was Raphael’s Final Act, a two-minute ode to Raphael’s power and the player’s impending doom, one that blends a creeping pipe-organ melody with grand orchestral swells, and imperious, mocking lyrics sung in part by Raphael’s voice actor. (Amusingly, if you cast the spell Silence on Raphael during the fight, his lyrics are removed from the music.)

In a game designed to generate memorable moments, Raphael’s Final Act stands out. And curiously, Larian isn’t the only developer to take inspiration from musicals this year. Numerous big games have used musical numbers to punctuate key moments. It is a fascinating trend, one that highlights developers’ confidence – because of all narrative modes, musical theatre leaves the least room for its creators to hide.

Cyberpunk 2077’s Phantom Liberty expansion is a spy thriller set in Night City’s fortified district of Dogtown, and asks the player to rescue an agent of the president from the clutches of a military dictator. The signature mission story is a glittering party at the top of a skyscraper, which the player must infiltrate. The centrepiece is Delicate Weapon, a song performed on stage by Cyberpunk’s fictional pop star Lizzy Wizzy, written and performed by the real-life musician Grimes.

“While designing this quest, our references included cult classics of the spy-thriller genre. That was the atmosphere we wanted to recreate – posh parties filled with beautiful people mingling, discussing extremely critical topics with bored voices,” says Konrad Chlasta, quest design coordinator at CD Projekt Red. “We knew that music is absolutely crucial, as each song in these kinds of iconic scenes is a story on its own.”

CD Projekt wanted to create a musical number that would draw players in, juxtaposing the dangerous reality of their situation as intruders into the scene. But creating a “live” musical act in a video game is no easy feat. Not only do you need the song to be convincing, the performance needs to be believable too, which is tricky to pull off with real-time animations. “Cinematic story cutscenes are one thing, but seeing unnatural movement in dancing and un-synced voice lines during songs are very easy to spot and would break the immersion immediately,” Chlasta says.

Putting together the Delicate Weapon sequence required input from virtually all game design disciplines: artists, animators, level designers, quest designers, cinematics, writers, programmers, not to mention the music itself. But the most crucial element in making the performance work was the timing. “One iteration had [the song] starting right as we entered the party, but that didn’t allow the player to actually interact with the guests or experience all the conversations,” Chlasta says. “We felt the perfect moment was right after the tone change – the moment the plan shifts; when an agent gets caught inside a net bigger than they had thought.”

In the final version, Lizzy’s performance begins right after you make contact with the agent you’re looking for. At this point, your preconceptions about where loyalties lie and what exactly is at stake suddenly shift, and you’re left to contemplate what it all means amid the dancing lights of Lizzie’s holograms. “I noticed most people watch the show and don’t just advance the plot right away, meaning the concert works as it’s supposed to,” Chlasta says. “It’s a pause before what comes next.”

Perhaps the most outrageous use of song as storytelling this year comes from Remedy Entertainment, the Finnish studio behind Alan Wake 2, in which a real Finnish band called Poets of The Fall composed numerous songs as the fictional rock trio Old Gods of Asgard – and performed them in-game.

“It’s been a long process for us, using music and songs as part of storytelling.” says Sam Lake, Remedy’s creative director. “For a long time now, I’ve wanted a musical sequence in our games.” In Alan Wake 2, Alan, a professional author, is trapped in the Dark Place, an alternate dimension where anything he writes can come to life. “The dream-like nature of the Dark Place gave us a beautiful opportunity to create [a musical moment], as the whole of the Dark Place can be seen as a mad fever dream of Alan Wake,” Lake adds.

Lake conceived a sequence where Alan’s life story would be told through a spectacular four-part musical number. “I did what I usually do in our collaboration with Poets of the Fall and wrote a rough poem of what the lyrics could be about, out of which Marko Saaresto [Poets’ lead vocalist and songwriter] created the actual lyrics.”

The resulting song is a nine-minute musical biopic titled Herald of Darkness. Remedy decided to blend live-action recordings of the performance with the in-game world, having the player wander through a stage set as the song plays on giant screens in the background. It was performed live by the game’s cast at LA’s Game Awards in December; Poets of the Fall, as Old Gods of Asgard, spent a week at No 18 in the album charts, meaning that the game’s fiction actually did alter reality.

Lake describes putting Alan Wake 2’s musical numbers together as “a massive and complex technical effort” that included not just the song performance and a choreographed dance performed by key members of the game’s cast, but also building the level through which the player experiences the musical. Nonetheless We Sing is undeniably the highlight of the game. Not only is it completely unexpected in a survival horror game, but it also tackles the story’s inherent silliness head on, turning what could be a weakness into a strength. “It felt like a perfect method of recapping Alan Wake’s character and story so far,” Lake says. “An exciting idea to surprise the player and show how crazy the Dark Place is as a setting.”

Remarkably, there’s an even more ambitious example of a game doing this in 2023. In August, Summerfall Studios released its debut title Stray Gods: The Roleplaying Musical. As the title suggests, Stray Gods is a fully fledged, interactive West End show, where the choices you make influence not only the trajectory of the story, but the direction of the songs.

“I’d toyed with the idea of an interactive musical back when I was still working for BioWare on Dragon Age: Inquisition,” says David Gaider, creative director and co-founder of Summerfall Studios. “It largely sticks to our strengths … dialogue, character, narrative – while expanding on that in a way I found intriguing. After all, how hard could it be to take branching dialogue and add music and timers? The answer, as it turned out, was ‘very’.”

Stray Gods puts players in the role of Grace, a young singer who inherits the power of the ancient Greek muse, enabling her to compel people to express their feelings and desires through song. But through this, she attracts the attention of the ancient Greek Gods, who accuse her of murdering the previous muse. To prove her innocence, Grace must discover the truth of what happened. In short, it’s a perfect story for a musical.

Unlike a traditional musical, players can make choices that influence Stray Gods’ story. Players can decide how a number should continue at various points during the performance. “The sheer difficulty of constructing the branching songs, from both a creative and design perspective, was huge,” Gaider says. Part of this was simply telling a video game narrative primarily through song. “There were so many differences when it came to making a song, rules regarding what made it actually a song as opposed to dialogue set to music.”

Creating a protagonist who felt consistent while also giving the player the freedom to make choices is a familiar problem in game design, but Gaider says the musical element exacerbated it. “A traditional musical is predicated on the protagonist having a clear arc, with dreams and hopes of their own. As soon as player agency is introduced, however things become more complicated.” Gaider points to Once More With Feeling, the famous musical episode of Buffy The Vampire Slayer, as a guiding light throughout Stray Gods’ development, because of “how it fundamentally changed how the episode’s narrative was constructed. Ultimately though, it was all a learning process. “We didn’t completely figure it out until we were almost done making the game.”

Stray Gods may have been, in Gaider’s own words, a “five-year investment of sweat and blood”, but the result is a truly unique combination of narrative role playing and musical theatre. The project has also shown Gaider the power music can have as a narrative device. “I had this theory, going in, that for all the romances I’d previously written in games that took hours and hours of dialogue, I could possibly do the same thing in a much shorter time with music,” he says. “Can I make the player fall in love with a character in the space of a single song? As it turns out, the answer was definitively yes.”

Video games have long understood the importance of music as an accompaniment to play, how it can set the mood for a particular level or encounter. But what these projects demonstrate is the potential music has when it’s more directly integrated into the story, when it’s made an active participant in the narrative, rather than a passive one. “I believe integrating songs in story driven games is a very effective way to amplify the impact of the narrative and bring it to a next level,” Slavov concludes. “We, as human beings, are prone to connect key moments in our lives with songs we used to listen to at that time. I believe it’s the same for songs in video games.”